Tag: evolution

A Sphinx Moth And Friends

Hummingbird In Flight In A Field Of Pink

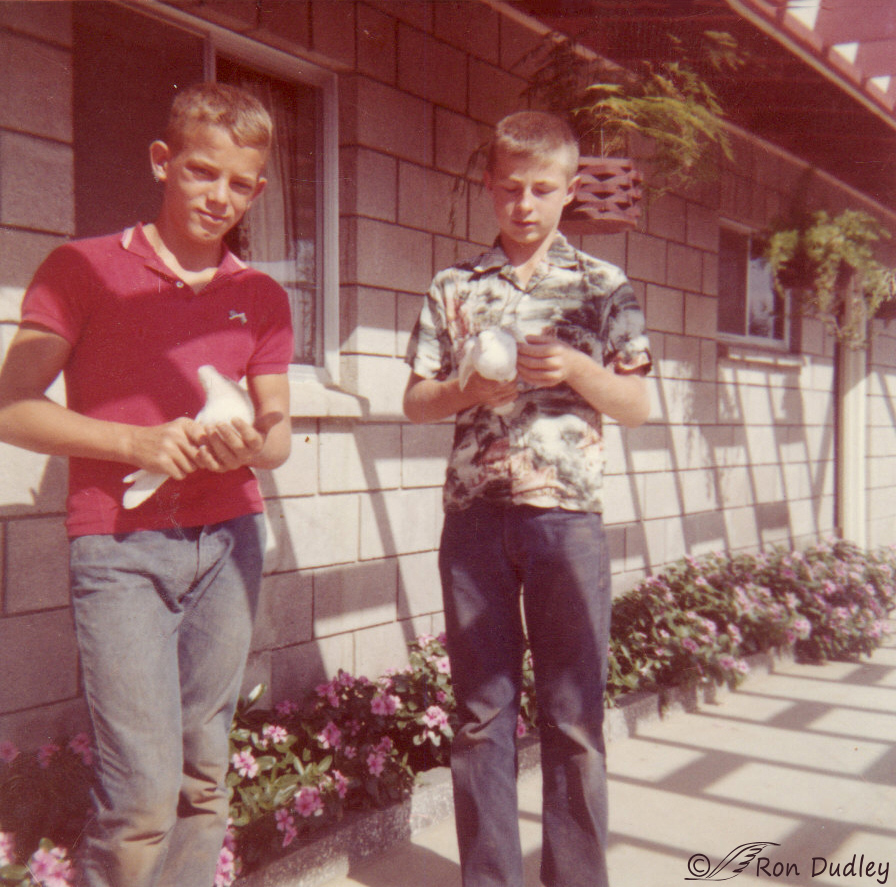

Darwin, Wedgwood Bone China, Pigeons And Human Inbreeding

Topsy-turvy Red-breasted Nuthatch

The Novel ‘Revenge’ Of The American Goldfinch

The Longest Great Horned Owl Ear Tufts I’ve Seen

Weather Loach – An Extreme Story Of Survival

Coyote Showing A Mouthful Of Teeth

My Half-baked Theory Regarding The Mechanics Of A Goldeneye Dive

Snowy Egret – “Golden Slippers” Running On Water

The Supracoracoideus – An Ingenious Adaptation For Flight

When I was teaching high school zoology I was fascinated by the many adaptations of birds for flight. Still am. One of them is a unique muscle arrangement that allows the return stroke of the wing while maintaining aerodynamic stability. I hope you’ll allow me a little change in direction with today’s post as I attempt to explain and illustrate one of the anatomical adaptations of birds for flight.

The Alula (bastard wing) Of A Kestrel In Flight

Many extinct and ancient relatives of modern birds had alulae, as do flies (insects of order diptera). I find it fascinating that evolutionary selection pressure has produced this structure in such diverse and relatively unrelated groups as birds and some flying insects. And that man has (once again) copied nature to solve a modern problem.

Nothing Wrong With A Butt Shot Now And Again…

This isn’t the sharpest image in my portfolio but it does intrigue me. A lot. Six days ago this Barn Owl made an unsuccessful plunge into the deep snow for a vole and soon after took off almost directly away from me. This is one of the images I got as it lifted off in the direction of its favorite hill-top perch – a “butt shot” to be sure but I’m fascinated by the wing angle and position. 1/3200, f/7.1, ISO 500, 500 f/4, 1.4 tc, natural light, not baited, set up or called in This shot caught the wings toward the end of the upstroke. The primary feathers at the end of the wings are in what appears to be an almost perfectly vertical position to allow for very little air resistance as they move to a higher position in preparation for the powered downstroke but the secondary feathers are pointed almost directly back at me. The skeletal structure of a bird’s wing is homologous (similar in position, structure, and evolutionary origin but not necessarily in function) to the forelimb of most other vertebrates (including humans) with a humerus, then radius and ulna, then metacarpals and finally phalanges at the end. Like humans, the joint between the radius/ulna and the metacarpals is the carpal or “wrist” joint (see here if you’re curious and/or confused by the anatomy). So the “wrist” is the joint between the primary and secondary wing feathers. Our wrist or carpal joint can be “bent” up or down and left or right but it cannot be rotated (try holding your…

Red-winged Blackbird With a Crossed Bill

This morning while out photographing birds at a local wildlife refuge I came across this Red-winged Blackbird with a strongly crossed bill, which of course is not typical of the species. I’ve seen a few mildly crossed bills in this and other species in the past but never one quite this pronounced in a species where it isn’t “normal”. Red-winged Blackbird with a crossed bill, perched on curley dock There are species of birds in North America that have crossed bills as a species trait – the Red Crossbill and the White-winged Crossbill. Their crossed bills are an adaptation for extracting seeds from cones. Seeing this RWBB with a crossed bill naturally got me thinking about evolution. Variations occur throughout nature since each individual inherits a different combination of genes from its parents. This particular variation would likely be selected against in RWBB’s and would not persist since they do not typically pry seeds from cones. However, one can see how this same variation in the ancestors of todays crossbills would be the genetic fuel for the crossed bill trait they all exhibit today. Ron