Adult Light Morph Swainson’s Hawk

My last post was of a juvenile light morph Swainson’s Hawk transitioning into a subadult, this bird is an adult light morph and my next post will be of a dark morph Swainson’s (and perhaps an intermediate morph also) – this is turning into a series…

Subadult Light Morph Swainson’s Hawk

I’m always interested in the color phases of the various raptors I encounter so when we found this subadult Light Morph Swainson’s Hawk on July 25 on our last trip to southwest Montana it got my attention. These worn young birds look white-headed in spring and early summer because of fading – much different from the adults.

Wildlife Photography While Pulling A Trailer Isn’t Easy

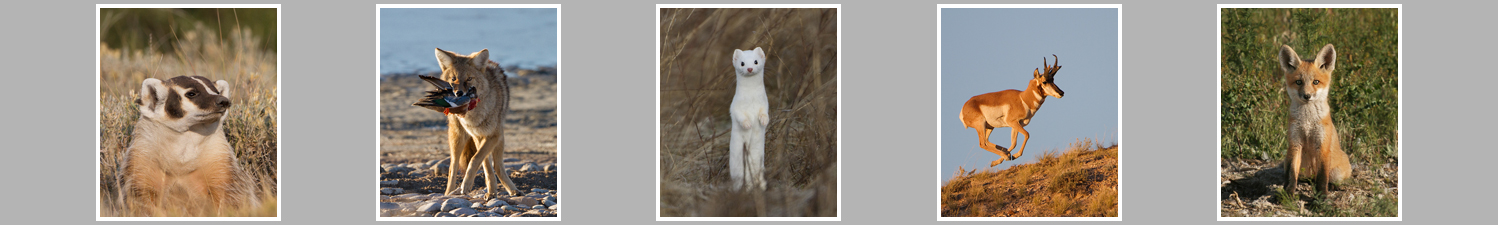

When we leave one of our favorite Montana camping spots for the long drive home it means almost 30 miles of extremely dusty dirt/gravel roads through prime bird and wildlife habitat before we hit pavement. We nearly always leave at sunrise in case there are photo opportunities on the way out – typically those opportunities include raptors on posts, poles or in flight, songbirds, elk, deer, pronghorn – even badgers.

If the roads are good (as they are this year) that drive takes at least an hour when I’m pulling my camping trailer but if we find wildlife, as we often do, it can take two hours or more. And believe me, photographing wildlife while you’re pulling a trailer is a bit of a challenge.

Juvenile Burrowing Owls Watching For “Incoming”

Banded Prairie Falcon – A Fascinating Update

Two days ago I posted about a very tame juvenile male Prairie Falcon I photographed last week in the Centennial Valley of Montana. The bird had two bands and I was extremely curious about where, when and why the falcon was banded and by whom so I asked for any insight my readers might have about the bands. Several of you jumped in with advice and suggestions, for which I’m much appreciative. But it was the superb sleuthing of my friend Mike Shaw that paid huge dividends. Mike did some research and learned that the colored band on the falcon (left foot) was issued to Doug Bell, Wildlife Program Manager for East Bay Regional Park District out of Oakland, California. On Tuesday, figuring that Doug might be interested in knowing that his California bird was now in the wilds of Montana, I emailed him with a link to that blog post and an offer to supply any more information about my encounter with that bird that he’d be interested in. I also asked him if he might tell me a little about his experience with the falcon. Yesterday Doug responded generously with information and photos. Since many of my readers expressed an interest in knowing about the history of this young bird I decided to update you with a new post rather than add an addendum to the previous post that many might not see. Besides, there’s a lot of new “stuff” here. Image property of East Bay Regional Park District – used by permission Doug and his team banded “my” Prairie Falcon…

Greater Sage Grouse In The Centennial Valley

I was driving the dirt roads while on the lookout for raptors (mostly) when out of the corner of my eye to the far right I saw (just barely) a flock of Mallards flush up from the barrow pit next to the road and just a few feet away. I gave them a quick glance and drove on but a couple of seconds later Mia hollered out from the back seat her patented “Stop, bird!”, which I immediately did. Turned out they weren’t Mallards, they were Sage Grouse – about a dozen of them.

The Tamest Prairie Falcon Of Them All

Montana Prairie Falcons And Hordes of Grasshoppers

I learned something last week in Montana’s Centennial Valley – Prairie Falcons eat insects.

In the past I’ve only seen them eat birds and small mammals and cursory research had backed up that observation but if you dig a little deeper in your research (Birds of North America Online, for example) you’ll find mention of lizards and insects being included in their diet. My friend (master falconer) Mark Runnels says that “Prairie Falcons will eat anything. In really bad years I have even heard of them feeding on carrion. You’ll never see a Peregrine do that!”

Juvenile Mountain Bluebird

Trumpeter Swan Pair With Six Cygnets

Trumpeter Swans are the largest of all North American waterfowl, weighing up to 30 pounds and having a wingspan of as much as 8 feet. It’s hard to imagine that by the 1930’s this species had been almost wiped out. In 1949 the Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said that the Trumpeter Swan was “the fourth rarest bird now remaining in America”. But thankfully recent intense swan restoration and management programs have brought the species back from the brink of extinction.