Perhaps the most significant event in vertebrate evolutionary history. We wouldn’t be here without it.

It’s hard to overstate how much of a game-changer it was when vertebrates first rose up from the waters and moved onshore about 390 million years ago. Many may not understand the reasons why it was perhaps the most significant event in vertebrate evolutionary history or know the adaptations more advanced vertebrates had to evolve before they could fully invade the land. So this retired zoology teacher is going to attempt to explain its significance and do it in not much more than the length of one of my typical blog posts.

I may or may not pull it off very well because I’m going to have to oversimplify and leave stuff out in order to keep things sufficiently brief. But I should be able to cover the highlights reasonably well and it’s something I’ve wanted to do for a very long time. So here goes.

There are two primary reasons why early vertebrates, fish and primitive amphibians, were confined to water:

- They had gills instead of lungs for the exchange of respiratory gases. Gills don’t work in air.

- But we’re going to concentrate on the second reason. Fish and amphibian eggs didn’t, and don’t to this day, have waterproof shells (think of frog eggs) so they’d dry out if laid on land. And as you’re about to see, a waterproof egg laid on land presents its own problems that had to be solved before the embryos inside could survive in eggs laid on land.

What was needed to make that transition was something like this – a waterproof shell. A friend and I found this apparently scavenged Long-billed Curlew egg on Antelope Island about 12 years ago.

The waterproof shell of modern birds and reptile eggs prevents the eggs from drying out. However, the shell also makes it more difficult for respiratory and metabolic wastes like carbon dioxide and urea to diffuse out of the egg and away from the developing embryo. Those wastes are toxic to the developing embryo.

So the development of the waterproof shell all by itself wouldn’t be sufficient to allow early vertebrates to fully invade the land without being tied to the water for reproduction.

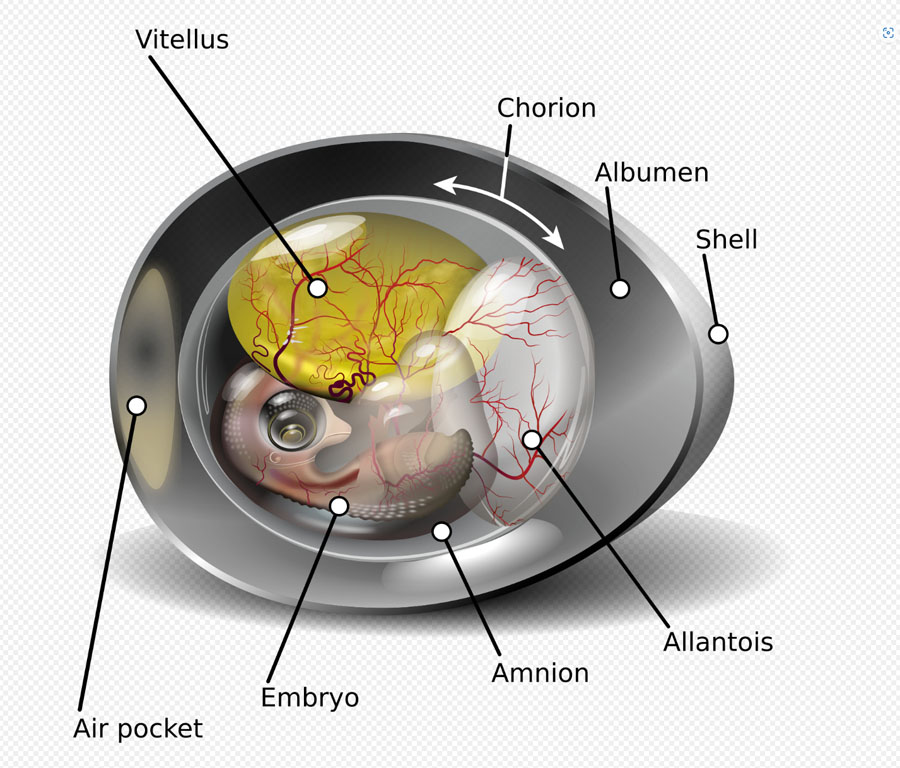

Chicken egg nine days after fertilization – Wikimedia Commons

This is what was required to solve all the problems – what is today called the amniote egg or land egg of modern birds and reptiles. The shell, plus four extraembryonic membranes, save the day.

- Shell – prevents the egg contents, including the developing embryo, from drying out.

- Yolk sac (vitellus) – food source for the developing embryo. This membrane isn’t new to land vertebrates. Early and present fish and amphibians had (have) it too.

- Amnion – a fluid filled sac that encloses the embryo in an aqueous environment, protecting it from shocks and adhesions.

- Allantois – stores metabolic wastes, isolating them from the embryo. Later on it also acts as a respiratory surface for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

- Chorion – the outermost membrane enclosing the entire system. It’s just below the shell (it’s the membrane you notice when you peel a hardboiled egg.

Note: Late in embryo development the allantois and chorion fuse to form the chorioallantoic membrane. Lying just below the porous shell, this vascular membrane serves as a provisional “lung”, allowing gas exchange through the shell.

There you have it. The development of the amniote egg is considered a pivotal moment in the evolution of vertebrates, perhaps the most significant event in vertebrate evolutionary history.

So in my view, we ought to know about it.

Ron

Note: All this explains how egg laying (oviparous) terrestrial vertebrates like reptiles and birds invaded and exploited a terrestrial environment but what about amphibians and mammals?

- Amphibians. They’re vertebrates but they don’t have a shelled egg. As their Class name suggests, amphibians are only partially terrestrial. Many can live on land as adults because they have small lungs to supplement the oxygen they obtain through their skin. But they’re tied to the water because the skin of most must be kept wet to keep it permeable to respiratory gases. But more importantly for us in this discussion, their eggs are shell-less so they must be laid in water to keep them from desiccating.

- Mammals. They’re vertebrates but with the exception of the Monotremes (platypus and echidnas) they don’t lay eggs. However, they do produce eggs – they’ve just evolved novel ways of nurturing their developing embryos in an aqueous environment inside the mother, so no shell is required.

Thank you for this excellent explanation!

All very interesting. Nice to have that natural history. Thanks for simplifying it.

Nice summary of this remarkable structure.

Thanks, Tony.

Hey Ron, I really had no idea that the work you do with the lens is so vital. I didn’t really know what Antelope Island was until I saw this video distributed by Yale360, EarthJustice and others. I haven’t seen the Great Salt Lake since I was a Boy Scout in the 60’s and, I was going to say swam, floated there. My interest in this valuable resource is renewed. Thanks for your documentary work of all the critters that live there.

“Vanishing Oasis” link to Venmo:

Link to EarthJustice article with video link:

https://earthjustice.org/article/saving-utahs-great-salt-lake-to-ward-off-an-ecological-collapse-and-public-health-disaster?

A very thought-provoking video, Lee, I recommend that others watch it too.

Wonderful post, Ron! Wouldn’t mind having more like this.

Yowser, appreciate this nice bonus, Ron! Yet another interesting and informative post. Rereading now as I finish the morning coffee. This morning another bonus was to hear ”quick, three beers!”, the song of the Olive-sided Flycatcher taking a pit stop in the gulch behind the house…

Thank you, Susan. And congrats on your flycatcher. The only empid flycatcher I can ID by its call is the Willow Flycatcher.

Thanks. Very nice summary. You accomplished in a short blog post much of the essence of what took me an entire chapter of my textbook to write. Of course, as a college level text I needed to go into far more detail but this is a great summary for the non-biology major. (In case anyone asks, the entire book was never completed. My energy got diverted for a time fighting bigger health issues. Once those were gone, some new priorities became more important.)

Thanks very much, Dan. Knowing you approve means a lot with this post. As you obviously know, it was a challenge to present coherently and accurately in such an abbreviated manner.

Thank you. Muchly. Some of it I knew and needed reminders. I do wonder about our platypus and echidnas though. I wonder why they went down a different evolutionary path…

“I do wonder about our platypus and echidnas though. I wonder why they went down a different evolutionary path.

EC, seems to me that when it comes to evolution, many, if not most of your mammals heard the beat of a different drummer…

True enough. I do love our beasties though. And our birds.

Thanks for extending my appreciation of the marvels of evolution.

You’re very welcome, Burrdoo.

This is an amazing awe inspiring fascinating process to read about. Thank you!

Very much appreciated, Eloise.

So in an unfertilized bird egg, are all the parts there except for the embryo? When you crack an egg and are separating the yolk (the vitellus?) from the “white” (albumen), what is the white wiggly piece that looks like an intestine – is that the allantois?

Remarkable! Thanks for the bio class to start the week!

“what is the white wiggly piece that looks like an intestine”

I enjoyed your description of it, Carolyn.

It’s called the chalaza and there are two of them. They suspend the yolk in the center of the white (the albumen). The function of the chalazae then is to hold the yolk in its proper place in the egg.

I understand that some folks remove them before cooking and eating an egg. I can’t imagine why.

Thank you. Fascinating!

A great review! I feel that nostalgia of being in your 10th grade biology class at South High in 1974. Also, an interesting companion to the book I’m currently reading, “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari. Fascinating.

Those were the days my friend! I miss ol’ South High and so many of the students. Sure glad we got back in touch again.

Thanks –very interesting.

Thanks, Laurie.

Interesting! Somewhere, MANY years ago, I seem to remember learning something about his tho not the added info on amphibians and Platypus etc. Chorion is a real PITA at times

Somewhere, MANY years ago, I seem to remember learning something about his tho not the added info on amphibians and Platypus etc. Chorion is a real PITA at times

Winter storm warning out for tomorrow into Wed. Hope there’s good moisture with it!

“Chorion is a real PITA at times’

Judy, I had that problem just yesterday when I was trying to peal eggs for an egg salad sandwich.

Thanks for this post. Though studied long ago in biology and anatomy classes my brain needed a refresher course! Very interesting!

Thanks, Joanne. Refresher courses can be almost as valuable as the first time around.

Learning is just a significant human process that takes place in the brain. It is something that should never cease – in my case it has been a 76 year journey so far. Thanks for reminding me to use it.

Mark, I’ve got a year on you (77) and I’m still learning. Including when I write a blog post like this one.

Wow. Always appreciate a lesson, and this one gives me a new perspective and appreciation for how things have developed.

Well done summary, just don’t send out a test.

It still blows my mind how in the face of entropy that the forces of life can evolve and adapt to propagate new life.

Thanks, Michael. Don’t worry – no test.