For the first six years of my bird photography “career” I rarely encountered banded birds but in the last two years or so I encounter them regularly, some species more than others. Usually when I see a bird with bands or transmitters strapped to their backs I don’t even click the shutter except for documentation purposes.

This image of a banded Burrowing Owl was taken on July 13. Based on my multiple encounters with them I’d estimate that almost 3/4 of the Burrowing Owls on Antelope Island are banded or have transmitters. Or both.

This shot of a banded juvenile Loggerhead Shrike was taken on July 6. Most (significantly over half) of the shrikes on the island are also banded.

Like this adult, some shrikes have an incredible amount of “jewelry” strapped to their legs.

This banded (look closely at its right leg) juvenile shrike landed on the tailgate of my pickup, also on the morning of July 6.

On July 15 I photographed this Caspian Tern at Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. If you look closely you’ll see that it’s banded.

Another shot of the same bird shows three bands on its left leg and one huge band on its right.

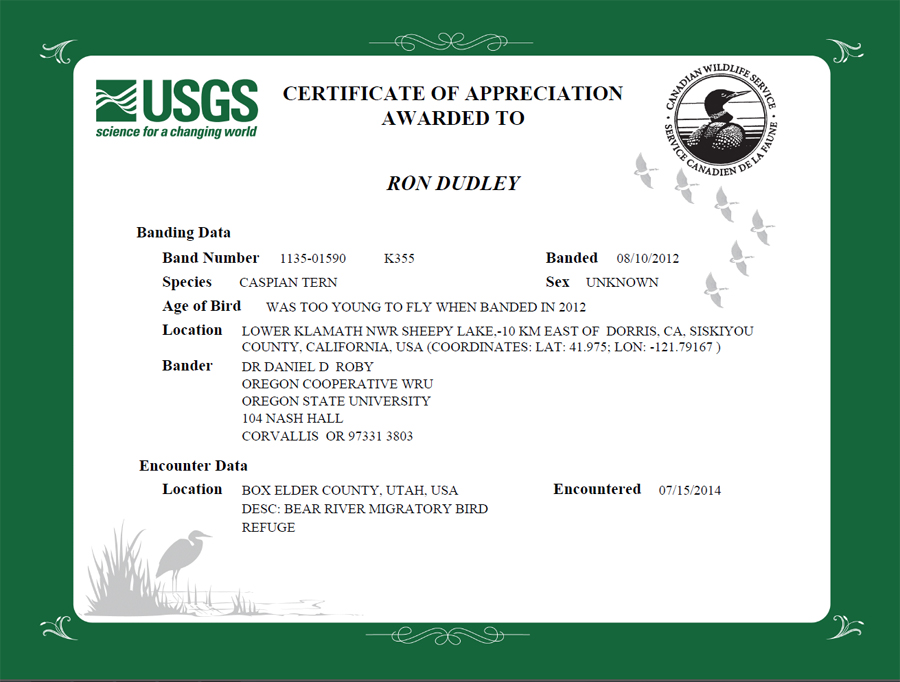

Last week I sent this image and reported the sighting to bandreports@usgs.gov…

and as they usually do they sent me this Certificate of Appreciation. I always find it interesting to see when and where the bird was banded and by whom. Obviously this kind of information can be of significant value in managing bird populations so I regularly report banded birds when I can read the numbers on the bands and I’ve long supported (publicly and otherwise) the banding efforts of legitimate banding organizations such as HawkWatch International and Great Salt Lake Institute (GSLI).

But my concerns about banding are growing. It’s a complicated and controversial subject – much too complex to go into in any detail here but I’m reading reports that suggest that in many cases banding and other tracking instruments may be doing more harm to birds than we ever knew – in some cases more harm than good. I’m aware of several banders that have at least some of the same concerns.

It’s a subject I’ll be following closely and likely be reporting on in the future.

Ron

Note: I’m off on another jaunt to Montana – duration unknown. I’ve scheduled posts in my absence but I’ll be without access to a computer so I won’t be responding to any comments, though I do receive your comments on my phone when I have a signal and I always enjoy them.

Wish me luck with the smoke from the fires in Washington, Oregon and Idaho – the prevailing wind direction is not helpful…

Jerry–what I REALLY want to know is whether “Hawk Identification” books, blogs and programs are really necessary…or can we just assume they are all “hawks” and let it go at that. It would certainly simplify things, especially where Sharp-shinned and Coopers are involved….

Is it really necessary to band so damned MANY?????????

I’m with Ellie Baby on this one. At this point, I have so many splinters in my bodacious butt, I’m afraid to back up to a fire!

I worked with a long-term project centered around Red-cockaded Woodpecker translocation. Because the species is so specialized to pristine Slash/Longleaf Pine forest that are regularly burned, they have become endangered and localized. We regularly banded these birds so that we could monitor their social groups throughout the year and use that information to carefully select young males – identified by their bands – to relocate to other populations. If not, their genetic diversity would eventually bottleneck within each population. Had we not had access to information gained from bands, we would not be able to do translocate these birds without capturing many other males and hoping that we haven’t harmed their complicated family groups and social structures.

Alex

Ron Banding has always bothered me but it seems like it is here to stay. I can see where it adds information both about climate and bird populations but think that sometimes the transmitters etc outweigh the bird. Esp when banding hummingbirds. Thanks for your thoughts

That’s funny Ron, I was going to write a blog post called “Bird Photography — Often an Unneccessary Evil”

Be my guest, Jerry. I’ve posted on that very subject several times myself.

Interesting comments! Have arrived in big sky country but hate.typing on my phone.

I too have concerns about banding, especially with Shrikes because they use thorns and barbed wire to hold their food. I know there is a group out of Canada trying to stop banding of Shrikes because they get caught on the thorns or fences. Have fun on Montana! We will be ther for a week in August. GTNP, Yellowstone, Beartooth Pass and Glacier! Can’t wait!!

Thanks for raising the issue, because it IS an important one. As a biologist I’ve helped with banding birds occasionally for a long time, and what is undeniable is sometimes it is pretty important to learn about endangered or soon to be endangered birds, for instance, and to do so we need to know who’s who and where they are going. But bands and transmitters are hardly without problem, and for any researcher to say they are ‘rarely’ a problem would assume they have followed each and every banded bird to confirm than, which of course is hardly the case. Just how essential to the population’s – or individual’s – future survival, short or long term, needs to be asked for every study that is done with bands/trasmitters. But it very rarely is to any real extent.

Scientists need to be reminded by the concerned public, and often, that in their vigor and eagerness for data, publications, career cache, tenure, job security, a raise, etc. whether or not to do an invasive study, even if that means banding or tagging ‘only’, is one of the most serious questions they need to be asking. Problem is it is rarely asked. I know of too many stories about lack of simple consideration of ethics and feasibility and potential harm that resulted in injury, suffering, or death of animals. But one example: when banding least Bell’s vireos for the USFWS recovery study – arguably a pretty important one considering they had recently been listed as endangered and people wanted to know where they wind up, overwinter, how many successfully fledge, etc., those of us monitoring the birds discovered that the wispy willow seed fluff that is a ubiquitous part of their habitat would get stuck and wrapped around their legs underneath and around their bands, resulting in swollen limbs and worse. The bander was a conscientious and careful researcher, but the problem occurred anyway.

Have a wonderful trip. And stay safe.

Banding? I am a fence sitter with splinters in my butt on this issue. Some positives, some negatives. And I wish that our behaviour (mostly) hadn’t diminished numbers to the point that banding is necessary/desirable/helpful.

What a coincidence Ron that you would publish this particular post the exact day that I decided to post a blog article discussing the importance of bird banding: http://www.wildlensinc.org/blog/2014/07/23/the-importance-of-bird-banding/.

I think in most cases when people talk about bird banding being harmful to birds, it is in the context of people either incorrectly placing bands on birds, or placing bands of the incorrect size. If bird banding is done correctly, it should, and most often does, have no deleterious effects on the individual banded. In the case of satellite and GPS transmitters, this is an entirely different story. There are many studies showing increased mortality rates in birds wearing GPS transmitters, however, there are many species of birds perfectly capable of wearing GPS transmitters, again if they are attached correctly. In many cases this is a species-specific issue.

The general public must know that the vast majority of scientists put the health and well-being of their avian study subjects above all else. If things such as bird bands and GPS transmitters are applied safely and correctly, they give scientists huge insights into the biological world that would otherwise go unseen. These insights can greatly advance our understanding of the avian world, as well as aid us in the conservation of many imperiled species.

Now that microchips can be very, very small (certainly smaller than the bands I’m seeing), it seems time to start running comparisons in the control arms of these studies for the effects of the various bands on morbidity and mortality. Certainly Burrowing Owls seem very irritated by their bands and spend time picking at the bands with heads down rather than up in surveillance for predators, which can be rather fatal for Burrowing Owls.

The flipper bands on king penguins when studied against control comparisons were found to be so deleterious that the import of the climate change data that was being studied is seriously called into question. This is referenced in a letter to Nature published online 12 January 2011, Nature 469, 203–206 (13 January 2011): Reliability of flipper-banded penguins as indicators of climate change In flipper tagged penguins.

“Here we show that banding of free-ranging king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) impairs both survival and reproduction, ultimately affecting population growth rate. Over the course of a 10-year longitudinal study, banded birds produced 39% fewer chicks and had a survival rate 16% lower than non-banded birds, demonstrating a massive long-term impact of banding and thus refuting the assumption that birds will ultimately adapt to being banded (ref6, 12..see article for refs). Indeed, banded birds still arrived later for breeding at the study site and had longer foraging trips even after 10 years. One of our major findings is that responses of flipper-banded penguins to climate variability (that is, changes in sea surface temperature and in the Southern Oscillation index) differ from those of non-banded birds. We show that only long-term investigations may allow an evaluation of the impact of flipper bands and that every major life-history trait can be affected, calling into question the banding schemes still going on. In addition, our understanding of the effects of climate change on marine ecosystems based on flipper-band data should be reconsidered.”

Penguins are large compared to the small birds we’ve seen carrying multiple external bands. Have the appropriate control studies been performed before extensive field banding was undertaken in the banding situations we are all seeing? I live in the San Francisco Bay Area and see many birds carrying bands out in the field, including more than half the observed birds on occasions.

I have some of the same misgivings articulated by Ron and others here. At the wildlife hospital where I volunteered, birds would occasionally come in with toes mangled from inept banding, bent backward and stuck in the band. Because of what I saw, my personal concern is the trauma associated with catching birds and then subjecting them to anyone with inadequate expertise. I’d like to see banding or tracking much more scrutinized in terms of necessity and attendant effects.

Do any of you here have experience with recreational banding events? By that I mean — as one example — I see a lot of photos from waterfowl hunting groups engaging young children in banding ducks, and I can’t help but cringe at the way I see some of the birds being held sometimes by their wings and so forth. It doesn’t inspire confidence in the banding overall.

Additionally, I have reported banded birds on several occasions, only to be told they were part of, say, a graduate study that is now complete. The birds wear these bands for the entirety of their lives, and are no longer tracked. I also know photographers who’ve seen birds dead and entangled by tracking devices like wing tags. It is obviously a very mixed bag of benefits and negatives. I like what Johanna writes about microchips and hope that less invasive and more easily tracked devices are, indeed, the wave and wings of the future.

I wish you the best on this trip, and hope the wind direction does not interfere with your photography.

I haven’t previously given a lot of thought to the banding issue, but seeing birds like your Caspian Tern and the Shrike with 4 bands makes me wonder about the necessity of doing so much banding. I don’t understand why it is necessary to put more than one band on a bird. It seems to me that once banded, other people studying those birds should be able to work off the band already on the bird. Large bands and/or large numbers of bands must affect the bird’s ability to fly and function normally in other ways. Definitely a disturbing subject. Thank you for opening my eyes to this issue.

Susan: Birds are most often banded with a single uniquely numbered federal aluminum band, but these bands are almost impossible to read in the field unless you actually recapture the bird to see it in the hand. When scientists are attempting to re-sight individual birds without capturing them, they will often put combinations of color bands on different legs to tell individuals apart from one another. In the vast majority of cases, these bands cause no ill-effects on the birds being studied. As with everything, there are always exceptions to this as one reader correctly commented with regards to banding King Penguins. Scientists have been banding birds for decades. I think with the new influx of interest in birds, birding, and bird photography (which is a great thing!) has made this more visible to the general public than ever before.

Thank you for helping me to understand banding. I have a lot to learn about the subject.

Hi! Great photo’s! That one bird has so many on its legs I am surprised it can even fly!

You deserve the Award! You have given so much to the care of all critters1 Have a great day!

Wonderful shots and information. Sometimes the best intentions go astray, is this the case with banding?

Charlotte

Have a great trip. Can’t wait to see your photos. I really dislike seeing so many bands on birds. Why are so many necessary? All those bands on a birds leg has to have a negative effect. Just my opinion. Safe travels Ron.

Hi Ron, an interesting and complicated subject with many factors at work. As just one small example, the Caspian Tern in your images appears to have been hatched from a small population that was created in the lower Klamath area as part of an effort to remove fish-eating birds from the Columbia River estuary. That relocation effort iitself is somewhat controversial and ties in with related practices of “managing” other piscivores such as sea lions(!). To say nothing about the dams…

Another thought – banding might be able to address/answer issues such as “it SEEMS as if there are fewer shrikes”, “we don’t see as many kestrels as before”, etc. that we, your readers, regularly raise. As I said, there are many factors at work but, as long as Homo sapiens engages in “wildlife management” (now there’s a topic that can stir folks up), there will be controversy. Like you, I think about this quite often, but never come away with an answer with which I am 100% comfortable. As a guy who spent his career problem-solving, I find it quite frustrating…

Thanks, and Bon voyage!

Cheers,

Dick